THE VERBAL ORDER:

SHABDAKALPA, A BENGALI HISTORICAL DICTIONARY

Sukanta Chaudhuri

Project Director, Shabdakalpa

Adapted from a paper read at the Forum Editorik Symposium, University of Gőttingen, Germany, June 2024

[This was the first presentation of Shabdakalpa to an international audience.]

This is the story of Shabdakalpa (roughly, ‘The Verbal Order’), a historical dictionary of the Bengali language being developed at the School of Cultural Texts and Records, an archival and research centre at Jadavpur University, Kolkata. We have worked on all kinds of digital archives, databases and websites, most notably Bichitra, a complete online archive and resource bank of the works of Rabindranath Tagore.

Let me start with a passage designed to make anyone cry off from compiling a historical dictionary. The Wikipedia article on the subject says:

Because of their size and scope, the compilation of historical dictionaries takes significantly longer than the compilation of general dictionaries. ... [T]he budget is often limited; historical dictionary projects often survive on a grant-to-grant basis ...

The challenge is immeasurably multiplied if the language is not in wide international currency (even if, as with Bengali, it has the seventh greatest number of native speakers in the world); if it is in a non-Latin alphabet of the ‘abugida’ type – that is to say, many letters are not written out in full but in curtailed conjunct form; and if funds for such projects are even harder to come by than in the developed West.

I cannot even say, like the first climbers of Mount Everest, that we are doing it ‘because it was there’: rather, because it was not there, and it seemed a good idea to have it. I should state that Bengali does have a historical dictionary in three print volumes, prepared by the Bangla Academy of Dhaka, Bangladesh. While this is an admirable pioneering work, I can soberly claim that our project is on a different scale and plane.

In fact, the lack of significant predecessors was an advantage, as it meant we had to start from scratch. Where earlier (usually pre-digital) dictionaries or corpora exist, as with major European languages, the editors very naturally use them, but this creates a methodological gap or fissure to be bridged. If we ever complete our Bengali project, it will be the world’s first born-digital historical dictionary to my knowledge.

The non-Latin font is no longer a problem with Bengali. The Avro keyboard software developed by Omicron Lab of Dhaka is almost universally used, and allows virtually all functions of the standard Roman keyboard. It’s a different matter when we come to OCR, which relates to the first part of my story.

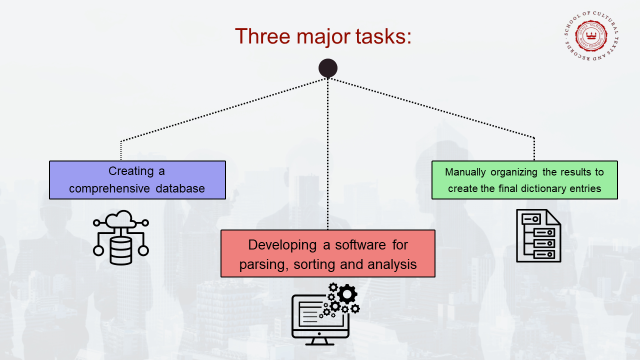

It is a story in three chapters, as our work involves three chief activities: compiling a comprehensive database, developing a software to process it, and analysing the results to create the final dictionary entries.

Two of these tasks, the first and the third, should largely be common to all languages with a Unicode-compliant alphabetical script. The second must be adapted to the grammar of each language, but our experience with Bengali should provide many leads. As multilingualism is one of the key themes of this conference, I would like to stress this wider applicability of our endeavour to a great many languages of the world.

The first task – or rather, the first of two simultaneous tasks – is to create a corpus or database of the widest possible range of texts of all periods and sources on all subjects. In practice, this largely means downloading material from the internet. Manual scanning would be impossibly long-drawn and expensive, transcription of manuscripts still more so. Fortunately, most major Bengali manuscript material has appeared in print. Fortunately too, another major archive, The Centre for Studies in Social Sciences Calcutta, has allowed us access to its extensive collection; and of course our School has its own archives, built up over twenty years.

Bengali printing effectively began at the start of the nineteenth century, so the quantum of material is much less than in the major European languages; but even so it is immense. Most of it is available online, usually as poor scans in PDF format. This has to be converted to plain text (notepad or .TXT) files, using Optical Character Recognition (OCR).

A good deal of material remains to be uploaded to the database, but the end is in sight. How will all this material be processed? This is the fun part of the story – a challenge it was really stimulating to face and, happily, solve.

Bengali is a highly inflected language, especially the verbs. It also has two different registers, the formal (sadhu) and colloquial (chalit). The former gradually fell out of use in course of the twentieth century, but is obviously important for a historical dictionary. All told, a Bengali verb might have some 150 or more different inflexions. As two common suffixes commonly follow them, the total count comes to 450-500.

We needed a program that could aggregate all these forms in a single record for the dictionary entry on that verb. This meant that before computers came into play, humans had to work out the entire paradigmatic structure (dhaturup) of the Bengali verb system, relying solely on morphology and not etymology and syntax: if such-and-such combination of letters indicating the base was followed immediately by such-and-such other combination indicating the inflexional ending, with nothing in between, the search output might (or might not) belong to the paradigm of a particular verb.

We thus worked out, at the pre-computational stage using the unaided human intelligence, a completely new classification of Bengali verbs, comprising 21 classes plus some anomalies. Each class had one or more bases formed of a particular combination of vowels and consonants, followed by a battery of inflexions.

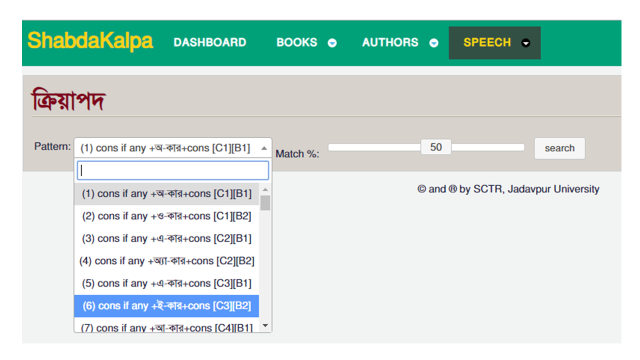

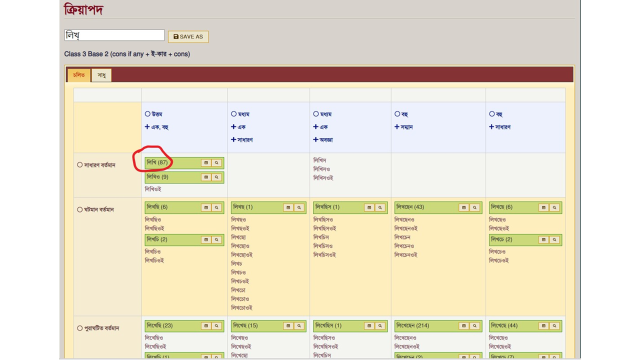

To use the software, you select a particular base of a particular class of verbs from the dropdown menu on the dashboard:

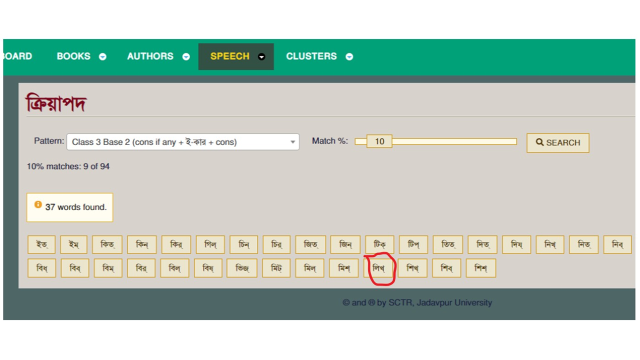

The result is a list of bases like this:

from which you click a particular base to open a table of all forms with that base.

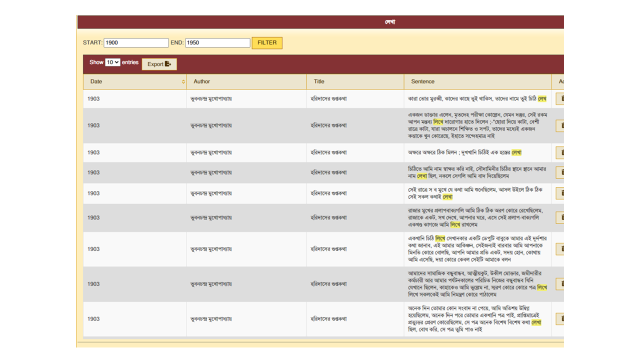

This table, for instance, is for লিখ্, one of the two bases of the verb লেখা. We can form a similar table for the other base লেখ্, and then club the two bases to create a single list of all examples of all forms of that verb comprising both bases.

Each example is complete with date, author, title and source sentence. The basis for the dictionary entry is complete. Pronouns are aggregated by a simpler version of the same process, and nouns with their various number and case endings by a different but analogous process.

This program is 100% ready. It is our greatest milestone to date, and makes us feel that we must continue, come what may.

We have resorted to minimalist solutions, partly for extreme paucity of funds but partly also for operational simplicity. Instead of a comprehensive database on a large internal server, we are creating a number of small databases, which can be populated simultaneously on separate computers, saving time. As each database becomes full, its word list is opened; the variant forms of verbs, nouns, pronouns or whatever are aggregated in the way described; and all entries relating to a single word are transferred to a simple MS Excel spreadsheet. That spreadsheet will be the datasheet which a philologist reviews to create the final dictionary entry. It will also incorporate additional sections and links — e.g., etymology, or links to one particular inflexional or orthographic form.

We are anxious to use every computational tool that might lighten or speed up the work. A doctoral student in our university’s Computer Science Department has designed a very efficient part of speech tagger, whereby we can separate homomorphs (words spelt alike) as long as they are different parts of speech.

Another program we are working on is to identify certain common structures in, say, 20,000 out of 300,000 instances of a common word. Once we have recorded the first few examples of such a use, we can leave the rest out of reckoning.

We can only talk of such strategies in the abstract, as it will be some time before we reach that point in our analysis. But at that tentative level, we have more or less set out the operating procedure. Most crucially, the basic technical matrix is complete and in use. Some cautious optimism may at last be in order.